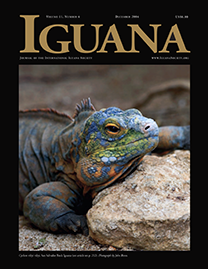

Status of the Jamaican Iguana (Cyclura collei)

Assessing 15 Years of Conservation Effort

Keywords:

Cyclura collei, Dry Forest Herpetofauna, Endangered Species, Headstarting, Jamaica, Predator Control, ConservationAbstract

Following its rediscovery in 1990 in the remote Hellshire Hills, the Jamaican Iguana (Cyclura collei) has been the focus of a sustained conservation effort aimed at securing the species’ short- and long-term survival. Major threats to the iguana’s persistence include habitat destruction by humans and predation by introduced mammals such as dogs, cats, and the Indian Mongoose.

Beginning in 1990 with field surveys of the remnant C. collei population and the formation of the Jamaican Iguana Research and Conservation Group (JIRCG), a variety of conservation measures have been implemented. Protection and monitoring of known nesting areas have facilitated the collection of founder stock for captive breeding and “headstart” programs, and have resulted in the collection, mark, and release of hundreds of C. collei hatchlings. As hedges against extinction in the wild, breeding nuclei of C. collei have been established at the Hope Zoo in Kingston and also at six U. S. zoos (Central Florida, Fort Worth, Gladys Porter in Brownsville, Texas, Indianapolis, San Diego, and Sedgwick County in Wichita, Kansas). The first captive-bred hatchlings were produced in September 2004 at the Hope Zoo. Adult-sized, headstarted C. collei reared at the Hope Zoo have been successfully repatriated into the Hellshire Hills, and we have now verified post-release survival of up to eight years. Egg-laying has been observed in repatriated females, suggesting that this zoo-based augmentation effort is having a positive effect on the remaining wild population.

Ongoing exotic predator removal efforts seek to maintain a conservation zone that is largely devoid of nonnative mammalian predators such as cats and mongooses. To date, hundreds of these invasive predators have been trapped and removed from the core C. collei area, and preliminary data suggest that the iguana may be benefiting from this predator control program. More recently (2003–2004), efforts to control feral dog and pig populations have been intensified.

Overall, the biological interventions directed at C. collei appear to have been highly successful. Unfortunately, C. collei’s dry forest habitat is at risk of ecological destruction. The remaining primary forest in Hellshire is under constant assault from the activities of illegal tree cutters, primarily charcoal burners. The JIRCG has protected a small portion of the forest in the vicinity of the known nesting areas and major iguana concentration, and attempts to discourage charcoal burners from penetrating farther into the undisturbed forest. If implemented, tabled government plans from the 1960s for large-scale commercial and residential development would likely cause the extinction of C. collei. Encouragingly, increased national and international appreciation of Hellshire’s stature as one of the finest remaining examples of Caribbean dry forest, together with considerable interest in the iguana’s plight, give hope that this unique ecosystem and its endangered occupants will receive adequate protection. Indeed, the Jamaican government’s declaration of the Portland Bight Protected Area (PBPA) in 1999 (including the Hellshire Hills and the Goat Islands) and the recent (2004) delegation of management authority to the Urban Development Corporation (UDC) is a positive step in that direction.